|

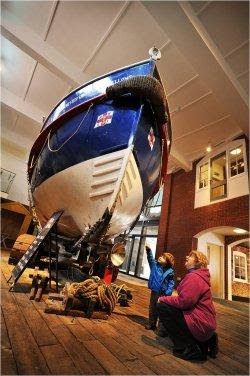

| Bothwell Castle |

In Which Jeremy Levett and family continue their explorations north o' the border.

We left the New Lanark youth hostel early on Sunday morning and followed the Clyde to Hamilton. First on the day’s list of entertainments was what remains of the country house Chatelherault. The various Dukes of Hamilton owned a truly absurd amount of land in Scotland, which when the Industrial Revolution rolled around turned out to contain extremely lucrative quantities of coal; some of the resulting funds were spent on a gigantic blinged-out country house, Chatelherault. In one of those Ironic Twists of Fate you don’t generally expect to happen in the real world, the ground beneath it then subsided due to coal mining, and much of the house had to be abandoned and demolished. All that remains today is the hunting lodge and kennels for the hounds.

That the kennels are a decent-sized, lavishly outfitted country-house-with-visitor-centre on their own (though at something of a slant) should say quite a lot about exactly how rich these people were. Further along the Clyde (and the book) was Bothwell Castle, gorgeous, crumbling, red sandstone, and the Hamilton Mausoleum, of same family, to bury each other and commemorate their, I dunno, money? Apparently the land-underminin’, rent-chargin’, miner-exploitin’, coat-turnin’ (switched sides a couple of times in various failed attempts at Scots independence) Hamiltons weren’t all that popular among the locals. No idea why.

|

| Livingstone does a spot of converting. |

Further doon the watter we explored the house Livingstone grew up in, a wonderful museum to intrepid exploring and missionary zeal littered with interesting artifacts and stories, and had a light but satisfying lunch at the visitor centre there. The fence around his garden was iron made in the shape of cowhide shields and assegai. The house was part of a tenement block attending another cotton mill, another New Lanark, that was torn down long ago; all that remains now is a scale model in the house, the house itself, and a weir a little upstream. The weir, with its more recent concrete salmon-leap stairs, was beginning to crumble beneath a cantilever bridge apparently made of big green pipes.

We dumped Oliver at the train station on a slow train that would eventually become a fast train to Bristol, at considerable expense. He has to be home to do Stage Crew stuff for a school production, which is going to be in a week or so at… the Edinburgh Fringe, when we’re in Edinburgh. Almost like we planned it that way. Then back on the road, heading north.

We stopped at part of the Antonine Wall, a walk which turned out to lead all the way to the Falkirk Wheel. The Antonine isn’t as much to look at as Hadrian’s Wall, just a shallow ditch and some oddly shaped bumps in the ground to the average eye. But when it comes to fortifications mine isn’t an average eye, and to me the place is still hellishly impressive a couple of millennia on. Roman defence strategy… Roman defence strategy is worth a post of its own. We didn’t venture all the way to the base of the Falkirk Wheel, or linger in the rain long enough for a boat to come and set it turning, but we saw the row of great hoops-on-sticks and the lifting apparatus clearly from the hill above. Back through the woods to the car, while express trains thundered by in both directions.

We headed for the Highlands, stopping briefly for tea at the Crieff Hydro, a huge, glorious booze-rehabilitation thing turned hotel, playing host to yet another wedding. People had been getting married at New Lanark and Chatelherault, and though Scots weddings are at least much more entertaining to look at than English weddings (all those kilts and highland bling) it was beginning to feel as though we were being stalked by a single sustained marriage party.

Finally, the Highlands proper. There seem to be two kinds. When in the valleys (or are they glens here?) it all seemed absolutely stereotypical postcard material; you couldn’t move for picturesque woods and oh-so-whimsical Victorian hunting lodge holiday castles sitting by meandering, babbling streamlets in the shadow of crags, with deer among the trees and big birds of prey turning slow circles overhead in every valley. But as soon as the roads started gaining some height, the entire landscape changed.

I was expecting the place to get more like Snowdonia further north, but where in Wales the glaciers carved the valleys apart and left pyramidal peaks and crag-rimmed horseshoes, here the ice sheets covered the mountaintops themselves, leaving the peaks and glens uniformly smooth and gently sloped. Over this endlessly rumpled landscape areas of grass and heather alternate in seemingly random shapes, leaving a patchwork green and brown like a bacterium’s-eye-view of a camouflage jacket. There were hardly any crofts, or cows, or straggly sheep. Most of the buildings were abandoned, lying in various states of disrepair. Some were simply missing windows and roof slates, some without roofs or walls altogether, some fell so long ago or were destroyed so thoroughly that they were noticeable only as slightly bigger patches of rocks among the low, knobbly lines that were once their attendant dry-stone walls. People have been suffering here for a very long time.

|

| The Falkirk Wheel (Photo by Dave Morris) |

We stopped at part of the Antonine Wall, a walk which turned out to lead all the way to the Falkirk Wheel. The Antonine isn’t as much to look at as Hadrian’s Wall, just a shallow ditch and some oddly shaped bumps in the ground to the average eye. But when it comes to fortifications mine isn’t an average eye, and to me the place is still hellishly impressive a couple of millennia on. Roman defence strategy… Roman defence strategy is worth a post of its own. We didn’t venture all the way to the base of the Falkirk Wheel, or linger in the rain long enough for a boat to come and set it turning, but we saw the row of great hoops-on-sticks and the lifting apparatus clearly from the hill above. Back through the woods to the car, while express trains thundered by in both directions.

We headed for the Highlands, stopping briefly for tea at the Crieff Hydro, a huge, glorious booze-rehabilitation thing turned hotel, playing host to yet another wedding. People had been getting married at New Lanark and Chatelherault, and though Scots weddings are at least much more entertaining to look at than English weddings (all those kilts and highland bling) it was beginning to feel as though we were being stalked by a single sustained marriage party.

Finally, the Highlands proper. There seem to be two kinds. When in the valleys (or are they glens here?) it all seemed absolutely stereotypical postcard material; you couldn’t move for picturesque woods and oh-so-whimsical Victorian hunting lodge holiday castles sitting by meandering, babbling streamlets in the shadow of crags, with deer among the trees and big birds of prey turning slow circles overhead in every valley. But as soon as the roads started gaining some height, the entire landscape changed.

I was expecting the place to get more like Snowdonia further north, but where in Wales the glaciers carved the valleys apart and left pyramidal peaks and crag-rimmed horseshoes, here the ice sheets covered the mountaintops themselves, leaving the peaks and glens uniformly smooth and gently sloped. Over this endlessly rumpled landscape areas of grass and heather alternate in seemingly random shapes, leaving a patchwork green and brown like a bacterium’s-eye-view of a camouflage jacket. There were hardly any crofts, or cows, or straggly sheep. Most of the buildings were abandoned, lying in various states of disrepair. Some were simply missing windows and roof slates, some without roofs or walls altogether, some fell so long ago or were destroyed so thoroughly that they were noticeable only as slightly bigger patches of rocks among the low, knobbly lines that were once their attendant dry-stone walls. People have been suffering here for a very long time.