By Andrew Gorton.

In April I started as a volunteer gallery steward at the ‘Mo’ museum. The ‘Mo’ is a recently opened museum in Sheringham, Norfolk. (One of its exhibits, the J.C. Madge, was discussed in an earlier article.) Some of its collection used to be on display in a row of cottages set back behind the shops of the main street – the cottages were sold to part-fund the new museum, now in a purpose-built building on the promenade. Mo, short for “Morag”, was the daughter of a local man who was heavily involved with the town in the late 19th century, and used to live on the site where the museum now stands.

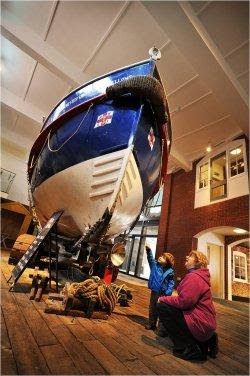

The star exhibits are unquestionably the boats. The town is unique in the world to posses 4 of its original lifeboats, 3 of which are housed in the Mo. The pulling and sailing lifeboat J.C. Madge was in service from 1904

The Madge was replaced in 1936 by the RNLB Foresters Centenary, and was Sheringham’s first motor lifeboat, powered by a 6-cylinder petrol engine. This boat served during World War II, and as this part of the coast saw a lot of air traffic, both Allied and German, the Centenary rescued more downed airmen than any other lifeboat in the country.

In 1961, the all-weather lifeboat Manchester Unity of Oddfellows took up the Centenary’s role. At 22 tons, it is by far the largest of the 3 lifeboats. A question I am regularly asked by visitors is how it was got into the building. They actually had to lower it in by crane before putting the roof on. There is a rather impressive video projection available showing the whole operation.

There are also 3 fishing boats built by the Emery family, who had a boatyard in Sheringham until 1981. The Emerys were famous for building their boats entirely by eye and without plans or drawings of any kind. Looking at these clinker built boats, you can really appreciate the skill and care that went into making them.

As a gallery steward, I have met a number of visitors, many of them who are or were locals, and I have learned a lot from their stories. There was the guy who went to school in Sheringham during the war and remembers the town being bombed. The town was one of the main routes to and from Germany , and enemy aircraft often ditched whatever loads they had left on their way back, hoping to hit the nearby army camp in Weybourne. This particular gentleman told me that the school parcelled out each class to separate buildings around Sheringham, in case the worse happened. Talk about not keeping all your eggs in one basket! Another gent in his 60s attended Sunday school in Sheringham as a boy, and recalls once helping 40 other people to launch the Centenary when the maroons went up. It must have been a pretty good excuse to skip school!

As well as recovering aircrew and civilians, and sadly the occasional body, the crew of the Centenary also salvaged whatever they could of the aircraft. One visitor told me he had parts of a fuel tank of a German aircraft that came down in the sea. His father had somehow managed to obtain them on the sly. According to this guy, it was from this particular aeroplane that the British got the secret for self-sealing fuel-tanks, a much prized piece of technology then.

I remember another visitor quite clearly. He had served on the Oddfellows lifeboat when it was operational, and was showing a friend around. Obviously this guy’s knowledge was impressive, and both his friend and I were duly impressed. As is often the way, this ex-lifeboatman was very modest, and even seemed uncomfortable with his friend’s genuine admiration.

All in all, it’s been a fascinating experience, and, if you’re interested, there may be more of the same in due course.

Andrew Gorton is an OU student, London born but now living on the North Norfolk Coast.

The Mo's website is www.sheringhammuseum.co.uk/

No comments:

Post a Comment